“It was already one in the morning…when, by the glimmer of the half-extinguished light, I saw the dull yellow eye of the creature open; it breathed hard, and a convulsive motion agitated its limbs… one hand was stretched out, seemingly to detain me, but I escaped and rushed downstairs. I took refuge in the courtyard… listening attentively, catching and fearing each sound as if it were to announce the approach of the demoniacal corpse to which I had so miserably given life(Shelley, 1818).”

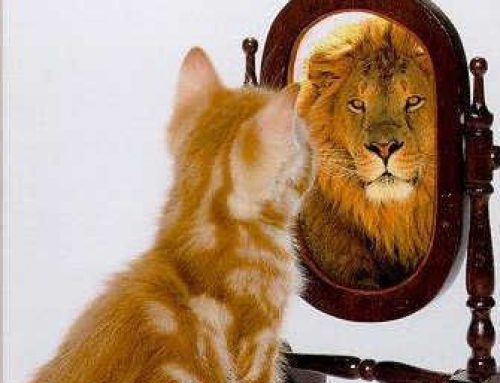

We can all recall the story of Dr. Frankenstein’s “monster”; for many of us, Dr. Frankenstein is the go-to image of a mad scientist who put together parts of corpses to create a monstrous beast (who, many may agree, is simply misunderstood). But what does ‘mad’ really mean? His ‘madness’ stemmed from his willingness to go beyond the boundaries in order to bring back our loved ones from the dead: to do something no one has ever done before. Aside from the controversy the creation of a being from corpses may entail, the overall theme is that outside-the-box creativity ‘requires’ an outside-the-box mind, which is oftentimes portrayed as mentally ill. These creative, ‘mad’ geniuses have also been described as eccentric, unconventional, imaginative – anything but the norm. It is true that there exists a well-studied relationship between extreme creativity and mental illness1; however, it is conflicted by many other studies that, on the contrary, suggest that mental health is just as importantly related to creativity. Due to the fact that such a great deal of attention has been paid to studying creativity in mental illness, the creative individuals who are able to mitigate their mental health are often overlooked and very underrepresented in literature and research1. Examples of such individuals include William Shakespeare, Albert Einstein, Aldous Huxley, Niels Bohr, Carl Jung and many more. It is not surprising, however, to continuously see media articles with the breaking news on which famous historical figure suffered from which mental illness, even though no evidence of such may exist. Most of these ‘diagnoses’ are made posthumously, where validity is often lacking, and should, thus, be considered with caution. It is almost as though we are looking for a reason that creativity is justified; inadvertently creating certain biases and, therefore, leading to a presumptuous approach towards those suffering from mental illness. Creativity in mental illness should stop being romanticized and seen as a sort of compensatory advantage. It not only overclouds the distress an individual suffering from a mental illness is in, but also propagates the misunderstanding that a disorder is necessary for creativity. Instead, the focus should be on how one’s mental health can positively benefit from participation in creative activities and self-expression. Additionally, our definition of creativity should be more malleable in recognizing the different forms that we can express ourselves in: creativity is about exploring not just the inside of self, but also the outside and can come about in a multitude of ways.

The role of creativity in improving not only mental, but also physical health, has now become a hot topic of research. Numerous studies have shown that creative self-expression has beneficial effects in improving mental and emotional wellbeing, alleviating physical conditions such as Parkinson’s and cancer, as well as aiding dementia2. Participating in art activities has also been linked to a slower cognitive decline by supporting and stimulating the growth of new neurons3. Specifically, visual art therapy is gaining lots of popularity as it has been shown to strengthen positive feelings and self-concept, reduce anxiety, depression and stress reactions4,5. When one participates in a creative activity, e.g. painting, their brain releases dopamine and serotonin: dopamine being a natural anti-depressant that is also known as the “happy hormone” while serotonin is important for calmness and emotional wellbeing. Both of these hormones, in normal amounts, work together to positively contribute to one’s mental state. Additionally, participating in a creative task has been related to a meditative state: by immersing yourself in a mind-engrossing activity, the mental chatter and chaos, which plagues many of us, is silenced as we focus on said activity. As a result, a more peaceful and happier state of mind is attained and reinforced with continued participation. It is not without reason that many meditation classes now offer art therapy events, such as paint nights and almost every bookstore sells adult colouring books. Even observing a creative activity has a positive effect; however, active participation is best.

For many of us (including yours truly), participation in creative activities declined with entrance into a post-secondary institution. This is mainly due to the fact that our performance is gauged by our ability to follow standardized testing with limited opportunities for outside-the-box thinking and expression. This is, unfortunately, further strengthened by increased stress, anxiety and fear – all of which are increased for students and are debilitating for any endeavour. If we followed the ‘popular’ belief that mental distress and illness equates to genius creativity, then many of us would be Van Goghs by now. Instead, the priority in the dialogue of creativity and mental health should be on how self-expression can improve the quality of our lives by bettering our psychological state. There are no rules about how one should be creative. There isn’t an instructions manual about how one can look up at the night sky or down at the many cracks in the pavement, appreciate its beauty and take a photo of it. Similarly, our creativity doesn’t even have to be related to art. You may make phenomenal cheesecakes, tell very funny jokes or you may have even found a creative way to toss your garbage into the trashcan across the room. Creativity comes in many forms – all of them are just as beneficial and meaningful. The moment that we, as a society, begin to have rigid definitions of what is creative and what is not, we halt exploration and evolution. Importantly, we prevent the mental and physical health benefits that creativity begets. Next time you feel like singing in the shower or dancing while you count the till at work, try it – your mind will thank you.

1= Pavitra, K. S., C. R. Chandrashekar, and Partha Choudhury. “Creativity and Mental Health: A Profile of Writers and Musicians.” Indian Journal of Psychiatry 49.1 (2007): 34–43. PMC.

2= Bolwerk, A., Mack-Andrick, J., Lang, F.R., Dörfler, A., and Maihöfner, C. “How Art Changes Your Brain: Differential Effects of Visual Art Production and Cognitive Art Evaluation on Functional Brain Connectivity.” PLoS ONE 9.7: e101035. (2014)

3= Madori, L.L., Melville, L., Stickney, G., Padoto, D., and Rodriguez, J. “Meditation and TTAP Method® with Residents Diagnosed with Early Stage Alzheimer’s Disease.” J Alzheimers Parkinsonism Dementia 1.1:003 (2016)

4= Malchiodi, C. A. (2013). Art therapy and health care. New York: Guilford Publications.

5= Walsh, S. M., Radcliffe, S., Castillo, S., Kumar, A., and Broschard, D. “A pilot-study to test the effects of art-making classes for family caregivers of patients with cancer.” Oncology Nursing Forum. (2007): E9–E16.

https://cdn-media-1.lifehack.org/wp-content/files/2017/07/31031815/creativity-boost.jpeg